Some words are used so often that they start to lose their meaning. “Biodiversity” is one of them. In a business context, it is often associated with pleasant images: a few birds, trees being planted, a meadow corner, a beehive on a rooftop. That is already something. But biodiversity is far broader, and far more concrete. It is the living fabric that holds together water, soils, fertility, pollination, flood regulation, and a territory’s ability to absorb shocks. Understanding this means moving from a “nice-to-have” topic to a matter of responsibility.

When we say “biodiversity,” what do we really mean?

Biodiversity is not scenery. It is not “nature” as something to admire from a distance. It is life, at all levels:

-

diversity within species (genetic diversity and adaptive capacity),

-

diversity between species (plants, animals, fungi, microorganisms),

-

diversity of ecosystems (grasslands, forests, rivers, wetlands, soils, wastelands).

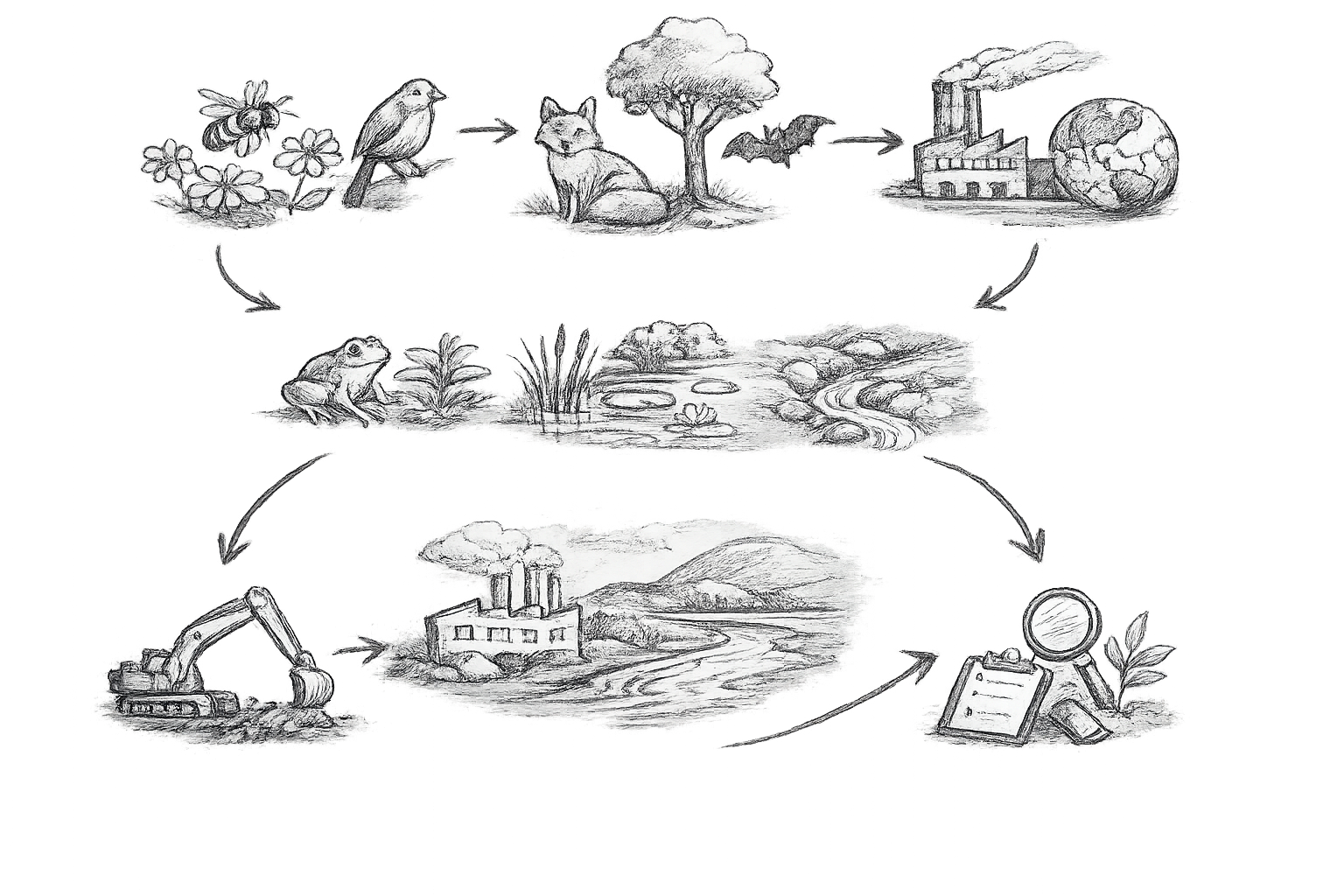

And above all (something often forgotten) biodiversity is not a checklist. It is a network.

The real value lies in invisible connections

What makes living systems resilient is the web of relationships.

A hedge is not “just” a hedge: it is a corridor, a refuge, a food source, a windbreak, a water regulator.

A wetland is not “just” a swamp: it is a filter, a sponge, a buffer against floods.

Soil is not “just” a surface: it is an entire world.

When these connections unravel, ecological functions collapse. And very quickly, this stops being abstract. It becomes about costs, risks, and vulnerability.

Why does this directly concern businesses?

Because, often without realizing it, businesses depend on living systems. Everyone does.

-

water, in both quantity and quality,

-

stable soils that absorb, store, and filter,

-

natural regulation (pollination, pest and disease control),

-

territories capable of coping with droughts and floods.

These are sometimes called ecosystem services. The term may sound technical, but the idea is simple: they are the quiet, everyday processes that make life (and economic activity) possible.

Two questions that change everything: dependencies and impacts

You do not need to be a biodiversity expert to take meaningful action. You just need to ask two honest questions:

1) What do we depend on?

Water, soils, raw materials, territorial stability, agricultural biodiversity…

Sometimes very local dependencies: a watershed, a groundwater table, a nearby forest, wetlands upstream.

2) What do we impact?

Land take and soil sealing, habitat fragmentation, night-time lighting, discharges and runoff, pesticide use, biodiversity, intensive purchasing (paper, timber, textiles, food), logistics.

This is often where reality becomes clear: biodiversity is not “a side project”, it is a way of reading reality.

Three common traps (and how to avoid them)

Trap #1: Confusing biodiversity with climate

The two are linked, but they are not the same. A climate-focused action can be neutral, beneficial (or harmful) to biodiversity depending on how it is designed. The two topics must work together, not replace each other.

Trap #2: Believing that planting trees is enough

Tree planting can be valuable, if done properly: suitable species, diversity, living soils, long-term management, monitoring. Otherwise, it risks becoming a communication exercise rather than an ecosystem.

Trap #3: Promising future “compensation”

In biodiversity, the robust sequence is simple:

avoid → reduce → restore (and only then contribute).

The most credible action is the damage that never happens.

Where to start, concretely, without getting lost

You do not need a perfect master plan. You need a solid first step.

-

Look at the site and its surroundings: water, soils, ecological connectivity, lighting, refuge areas.

-

Identify 3 to 5 major pressures: those that truly make a difference.

-

Choose high-impact actions: often night lighting, water management, soil permeability, land take, green space management.

-

Set up simple monitoring: not for show, but to learn and adjust.

Credibility comes from continuity: acting, measuring, improving and acknowledging what is difficult.

What does a well-formulated biodiversity objective look like?

A strong objective is grounded in reality:

-

a place (which site?),

-

a lever (lighting, depaving, land management, purchasing…),

-

a clear indicator (simple and understandable),

-

a timeline and a responsible owner.

Biodiversity does not respond to slogans. It responds to care, precision, and time.

Conclusion

In business, biodiversity is not about “doing something green.”

It is about learning to see what truly supports our activities: water, soils, habitats, and invisible connections. Once this is understood, CSR changes in nature: it becomes less decorative, more responsible, and paradoxically, simpler. Because we finally know where to act.